With the pandemic continuing throughout 2021, it was another highly unusual year for cinema, as movie theaters here in New England faced lengthy (and often quite sudden) shutdowns and hesitant re-openings as public health parameters shifted locally and globally. Some cinemas and theater chains didn’t survive those changes and the subsequent loss of film audiences when more people retreated to streaming films online at home. Somehow, I was able to keep myself going to see movies in person at cinemas throughout nearly the entire year, though the rollout of worthwhile new films was slow and halting, as film companies carefully measured and re-calibrated what might be worth releasing and when. Release schedules continued to get jostled around as film releases were postponed and timed for when they might get the best kind of audience response at the box office. Therefore, as with my year-end post for 2020, just three movies lingered with me most throughout 2021, and in each case, I was drawn to them as much for their subtle emotional pull as for their narrative and visual craft. I felt like these movies spoke to my own levels of sadness at the ongoing state of the world and offered some consolation and distant yet intimate company via their artistry.

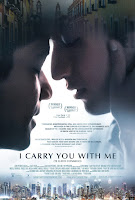

It’s fitting that Heidi Ewing’s moving and relatively little-seen gay Mexican immigrant romantic saga I Carry You with Me was my favorite movie in a year when Jane Campion’s much-lauded, quasi-gay Western tragic epic The Power of the Dog could win Best Picture (and Best Director) at the Oscars. While Campion’s novel-like film is certainly finely made, intricately deployed, and superbly acted, its mystifying effect on the mostly straight audience that I saw it with seemed to be its intended goal, whereas a gay male viewer like me could easily see the planted curveballs coming. I Carry You with Me has fewer tricks up its sleeve, perhaps because it wears its heart more openly there, which isn’t to say that it’s a simple story, nor one that’s simply conceived. Based on the actual relationship of two of Ewing’s gay friends, Iván (Armando Espitia) and Gerardo (Christian Vásquez), a chef and a teacher, respectively, the film follows the two young men from their initial meeting at a club in Puebla, Mexico in the ’80s through their struggles to immigrate to New York City, to nearly the present day and their celebration of their time together running a restaurant there. I was engrossed in their story and right with them every step of the way, and the immigration scenes especially were some of most powerful I’ve seen on film. Their romance is equally well-developed and sincere, at a time when more movies still need that sort of earnest depiction of gay male characters.

Drama and hardship aren’t left out of the picture, of course, since Iván is a closeted and married father of a young son when he and Gerardo first meet, and both face intense and overt familial homophobia during their youth and upbringings. Machismo and the masculine pressure to conform in erasing any form of effeminacy in boys runs rampant throughout the culture, one in which fathers like Gerardo’s and Iván’s are pressured to punish and cruelly abandon their own young sons for the boys’ inability to meet their society’s unfair masculine standards. For that reason, it’s also quite uplifting and reaffirming to watch a gay film in which the characters can all transcend those hardships and eventually overcome their obstacles to actualize their dreams. The moment when Iván’s chance at fulfilling his ambitions finally arrives by happenstance in the kitchen of a Manhattan restaurant was perhaps the most moved I felt at the cinema this past year.

The best innovation of the movie is the twist in its latter half, when we meet the characters in their older incarnations; rather than using actors, all of the characters are simply portrayed at that point in the film by the real-life people themselves. It’s the perfect way for Ewing to balance the often dreamlike tone of the film’s first half and to allow these two men to claim their own story, as well as giving the audience a true opportunity to get to know them. (Also, it makes sense that the director would shift into documentary mode since her best-known previous films were documentaries.) Despite the acclaim that I Carry You with Me received at the Sundance Film Festival and at a few other awards ceremonies, it’s dispiriting that the movie earned under $200,000 at the box office upon its official mid-year release, which had been delayed by several months. Cinemas across much of the country were still just beginning to open up again at that point, and audiences were still somewhat wary of going to see movies in person at a movie theater, so clearly those factors were part of why few people have found the film. In an ideal world that would surely not be the case because this is an artfully rendered and deeply human movie that deserves to be widely seen.

Robin Wright’s Land, her feature directorial debut, was actually one of the first films that I saw at a cinema up in Maine in 2021, way back in late February, just after a shutdown of several months had closed the cinemas there. I didn’t expect to be as emotionally affected by the movie as I was, probably due to a combination of the film’s subject matter, the circumstances in which I watched it by myself in the back row of an almost empty theater, and mainly seeing it at the time when I did, during the first winter of isolation and solitude at the worst point in the pandemic. Just as central to the movie’s power is Wright’s enduring performance as Edee, full of soul and gravity, which lasts for the entire length of the film. Even more impressive, perhaps, is how nearly all of the movie takes place at a single location, inside and around a small cabin high up in the wilderness of the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming (though the actual filming location was in Alberta, Canada).

Edee has retreated there from city life, determined to live in the mountains alone on her own terms, in spite of the difficult conditions and warnings from a local man who drives her up the mountain and hesitantly drops her off. Much to its advantage, the film doesn’t reveal the reason why Edee has fled her former life until almost the end of the film; she only mentions that she didn’t want to be around any other people. She experiences some peace in autumn and tries to grow more accustomed to living on the land. As the season turns brutal and her winter alone on the mountain takes serious hold, however, her situation indeed disintegrates rapidly from grim to desperate to catastrophic. On some level, we know that her plan for this to happen was semi-intentional, that she in fact no longer wanted to be alive, and yet she’s able to force herself to continue to survive by focusing on thoughts of her sister Emma, to whom she speaks early in the movie before going permanently off the grid.

Her character comes quite close to meeting a painfully gruesome and untimely end, and then she’s saved by a shy and kind-hearted local hunter named Miguel (played by the extraordinary Mexican actor Demián Bichir) and his caring but skeptical friend Alawa (Sarah Dawn Pledge), who’s a nurse in a nearby town. After Edee’s health gradually returns, Edee and Miguel become friendly over time and begin to open up to one another, with all the right notes of chemistry and trust between the actors, until Miguel eventually disappears from Edee’s life without notice or explanation. She soon persuades herself to try to track him down, once she’s feeling fortified enough to interact with other human beings again and face civilization. I typically resist movies that seem to pile on the heaviness, but where the film went next in briefly re-connecting Edee with Miguel made perfect sense to me, again an absolute testament to the strength of the acting. By the end, the movie becomes a study in grief and how we navigate it, share it, help each other survive it, and then if we’re lucky, how we attempt to emerge from the shadow of it and move on. Although the source of Edee’s grief is far more tragic than anything that I’ve ever lived through, I related instantly and intuitively to her feeling of being unable to persist anymore, and I felt inspired by how she finds a sense of resolve through her friendship with Miguel to gently push herself forward. Not many films have made me cry twice, but Land was one of them.

The Green Knight, based on the medieval English narrative poem about young Sir Gawain, is the latest film that I’ve loved by David Lowery, who’s among the best American filmmakers working today. As with his previous films A Ghost Story and The Old Man & the Gun, Lowery again constructs a picaresque adventure tale in a way that’s never really been presented before, handling the inherent slipperiness of time and the scope of humanity in relation to it with both inventiveness and a relaxed sensibility that embraces subtlety and abstraction. His relationship to the original tale of Sir Gawain is grounded enough for all the signposts of the legendary Arthurian romance to remain recognizable, yet he reimagines and expands on plenty of the details to place his own cinematic mark on the text. The casting of Dev Patel as Sir Gawain, certainly, puts a significant contemporary spin on Gawain’s journey to find the Green Chapel where the treelike and thick-trunked Green Knight (resonantly voiced by Ralph Ineson) lushly resides, after Gawain swiftly beheaded him as a challenge during a dinnertime tale-telling at his uncle King Arthur’s Christmas feast. The deal is that the Green Knight will then return the blow and strike Sir Gawain’s neck to behead him in exchange exactly one year later.

From the importance of honor to the enduring power of nature, the various literary meanings and interpretations linger as echoes throughout the movie, while Sir Gawain’s own legend spreads throughout the land and he becomes a kind of medieval celebrity whose quirky, youthful abandon makes him crush-worthy and enviable. Puppet shows pop up in towns across the countryside, where children crowd in to watch playful re-enactments of the Green Knight’s beheading and foreshadow the one that’s predicted to befall Sir Gawain in return. Along his winding quest to find the Green Chapel, Gawain encounters a skeleton at the crossroads swaying in a rusty iron cage, a band of punky thieves and swindlers who plunder his goods and leave him for dead, an ominous talking fox as his somewhat faithful guide and sidekick, naked giants who roam silently across the land, and a Gothic castle with a Lord (Joel Edgerton) and Lady (Alicia Vikander) who share a seductive interest in Sir Gawain that’s both platonic and sexual, prompting a rather special appearance of Gawain’s magical green cloth belt that gives him his trademark brand of mojo throughout the film. Vikander appears in two roles in the movie: as the mysterious Lady who heightens Sir Gawain’s erotic experiences on a new and more electric level, while having also portrayed his peasant lover Essel earlier in the film.

The style of the movie reminded me more authentically of the totally awesome ’80s adventure tales like Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal than any other movie I’ve seen since then, though scores of other films have attempted to approximate that winning formula and fallen short of achieving it. (Lowery has also professed to being a major fan of Ron Howard’s 1988 fantasy epic Willow.) But the detail-rich imagery and mesmerizing auras that Lowery evokes throughout The Green Knight are far more ambitious and maturely realized than any of its well-meaning predecessors. The payoff when Sir Gawain finally arrives to kneel before the Green Knight in the secluded oasis of his Green Chapel feels both knowingly subdued and grandly opulent. It’s a finale that takes its time with plenty of silence and a sense of dutiful purpose, before it segues via Sir Gawain’s momentary panic into one of the greatest “my life flashed before my eyes” sequences that’s ever been committed to film, as Gawain is plunged headlong into ruling his own kingdom and the ensuing waves of public chaos and familial tragedy and personal loss. How the movie allows Sir Gawain and the Green Knight to peacefully part ways and take their leave of one another aspires to a higher notion of storytelling. Rather than simply proclaiming Gawain’s honor for his courage and willingness to lay down his life as promised, the film’s ending also asks us what it means to let someone fulfill his own narrative mission, as well as what it means to have mercy on the brave and vulnerable who surround us.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)