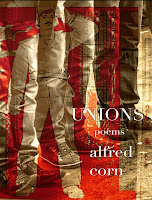

Unions,

Alfred Corn’s eleventh book of poetry, is his most accessible collection. The poems are still diverse and

demanding in their references and allusions, as well as in their variety of

forms, but those aspects don’t call attention to themselves, instead taking a

relaxed approach and inviting the reader to follow suit. It might also be because I’m currently

twice the age I was when I first read Corn’s poetry as an undergraduate

twenty years ago that the density of references ceases to distract me; now, I

recognize and understand the majority of them. I can better appreciate, too, Corn’s deft sleights of hand in

slipping them discreetly into his poems.

This

is an elegantly structured and sequenced volume, and its title motif is

intentionally woven through the book.

Among the collection’s myriad kinds of unions are transatlantic journeys to places that figure into roughly a fourth of the poems. The epic “Eleven Londons” recalls in close detail a series

of extended stays in the city over a period of four decades, carefully documenting

the sociocultural changes that took place in the author’s life, from the days

of Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison to debates over same-sex marriage and

post-9/11 wariness.

“A

city is a person,” writes Corn midway through the poem, and its segments,

constructed like free-flowing journal entries, are built around that notion;

the city changes as much as the poem’s author and the culture that surrounds

them both, just as his perspective on all of it changes simultaneously. A steady, informal rhythmic

underpinning that’s reminiscent of Derek Walcott’s lines keeps the sum of the

parts intact. Having visited

London annually each spring myself for the past two decades, I matched much of

my own catalog of memories with Corn’s:

Charing Cross, the National Portrait Gallery, Camden Lock, Regent’s

Park, Little Venice, Covent Garden, the bounty of West End theatrical productions. We’ve even seen some of the same shows.

Among

the book’s other United Kingdom-based poems, I particularly like “Bloody,” an

incisive etymology of that curious English adverb and its lack of (polite)

American counterparts. In a jaunt

across the Irish Sea, “Dublin Night” is also indelibly memorable and haunting,

with its lone shadow of a figure drifting through the bustling center of the

town in darkness, wondering if it might be best to disappear into the black

water running under a bridge.

Despite

such solitary glimpses, there are also, certainly, interpersonal unions

represented at points throughout the volume — friendships (“Bob”), rivalries

(“Doppelgänger”), romances (“In Half-Light”), sexual relationships (“Möbius

Strip”). But among the interpersonal

poems, the most impressive and intriguing one for me is “Common Dwelling,” a

poem about near-strangers, one’s neighbors residing in the hive of a communal

building. We live in a world in

which fewer and fewer people can afford to purchase a house, so it’s a scenario

that almost all of us can relate to:

“the enviable neighbor couple / who shift and stir less than an arm’s

length / behind the headboard, their murmurs / sifting into consciousness / as

though no sheetrock intervened.” No other poem that I know of conveys that

uneasy form of sonic intimacy so effectively. Or this:

“Heavy

boots not muted by rugs clunk

about

on the floor above. Months

of

obstinate slogging guarantee

their

pace would instantly anywhere

be

recognized, if not the pacer.

Odd

moments in the day he launches

his

campaign with a ruckus that feels

coercive,

sure, but on behalf of what?”

Formally, Corn turns in many different directions in Unions with skillful subtlety. In addition to plenty of free verse, there are several poems in rhymed couplets and quatrains, a few semi-sonnets, a trenchant villanelle about growing older, a poem written in Sapphic syllabic stanzas, even a sort of vertical palindrome. Another kind of form arises from thematically strategic pairings of poems that make the pieces resonate more deeply in sequence. For instance, a contemplation of the great pessimists from history and literature is followed by an existential meditation on the cast-off, broken wreckage out behind a pottery kiln, a scene of scattered fragmentation that nevertheless maintains its own sense of beauty.

The

same image could be applied to the American and global political landscapes as

Corn aptly describes them. From

allegorically political poems like “The Wall” to more direct and pointed indictments

like “Cascade of Faces,” Corn navigates back and forth between a citizen’s

commentary and active resistance.

Yet he always seems to emphasize human beings’ ongoing responsibility to

each other, ultimately, even if our contemporary cybernetic world makes those

connections ironically more difficult to forge. Today, our potential unions often throw our loneliness and

solitude into stark relief within “the musicosmic comedy of time.”

That

solitude takes center stage in “Hunting Season,” probably my favorite poem from

the collection. Several

alternating strands of imagery — an approaching thunderstorm, a man out walking

his dog, another listening to a classical composition on the radio while watching

from a window — escalate to a powerful crescendo that suggests imagination, even

imagination into some distant residual memory of a past life in ancient times,

may be the only real remedy and redemption. Just like in the rest of Corn’s work itself, music is the vehicle,

of course, that gets this poem’s speaker there: “Sing, goddess. / Lightheaded, I’m ready to be torn apart.”

The

poem also suggests that our increasingly technological existence will only ever

carry us back to nature, which is where the book begins, with a gorgeous ode to

the wind titled “All It Is.” “Any

terrain you find arises from all / that came before,” Corn surmises, after

tracing a breeze that makes its way through treetops and over wetlands. The same could be said of how this book

itself came to be, arising from all of Corn’s books, poems, and experiences

that came before. One more union,

then, or rather, many unions across the vast divisions of time and space. As Corn closes one poem early in the

collection, “Since what divides things joins them, too, united.”